Tales from the Dagshai jail museum

Cellular memory: stories of exiles and prisoners at the Dagshai jail museum

Dagshai, a small, peaceful town in Himachal Pradesh, hides a dark and powerful past. Perched high in the mountains, it once held criminals, rebels, and even famous prisoners in its cold, dark jail. The Dagshai prison, built by the British in 1849, is now a museum, but its walls still whisper stories of pain, bravery, and exile.

The town's name itself has a strange and ancient origin. In the Mughal period, criminals were sent into these dense, forested mountains as a form of punishment. Before sending them away, their foreheads were branded with a royal mark — called daag-e-shahi, which means "mark of the emperor." Over time, this name evolved into "Dagshai," and the area continued its connection to punishment and exile.

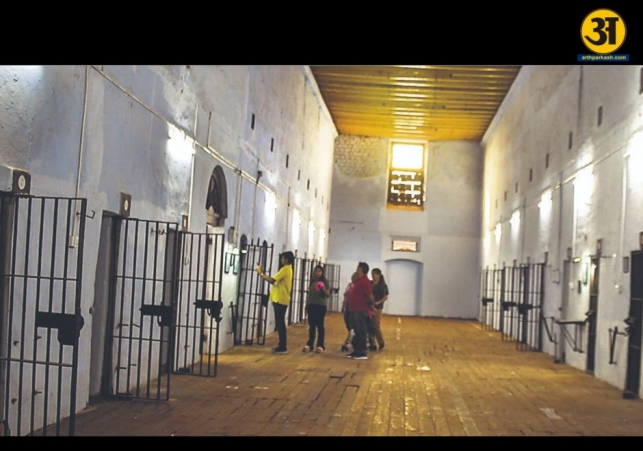

The prison was a secure and frightening place. There were 54 small, narrow cells. Each one was designed to break the spirit of the prisoner. The cells had thick stone walls, very little light, and just one window — which was also blocked with heavy grills. There were no comforts, no furniture, and no chance to escape.

The gallows house still stands nearby — a dark reminder of the many lives lost there. Executions also happened by firing squads. One well-known victim was a 20-year-old Irish soldier named James Daly. He had rebelled against British officers in 1920 and was shot for it. Many other Irish soldiers from the Connaught Rangers, who refused to obey their English officers, were also locked up in Dagshai.

In the same year, 1920, Indian Gorkha soldiers who had joined the British Army also revolted in the surrounding areas. Those who fought in the First War of Indian Independence in 1857 were among the first Indians locked up in Dagshai. Many of them were brutally punished for rising against British rule.

Perhaps the most infamous name in the list of prisoners is Nathuram Godse — the man who killed Mahatma Gandhi. Though he was not held there long, he did spend one cold, sleepless night in one of the cells on his way to Shimla for his trial.

Restoring a forgotten prison

Today, Dagshai jail has been turned into a museum, but the haunting silence and heavy history remain. The cells are still dark and claustrophobic. A torture room inside still has iron chains hanging on the walls — used to suspend prisoners who refused to follow orders. The worst rebels were thrown into a cage-like space, just 3 feet wide, with iron bars in front. They were given only dry bread and water to survive.

As we walked through the jail, guided by a strong, silent army guide, the lights suddenly went out. The prison was plunged into darkness, just like in the days when real prisoners were locked in. The guide whispered stories in the dim light — stories of pain, sorrow, courage, and even madness. No prisoner had ever escaped from Dagshai, he said. The only way out was through death — into the small cemetery on the jail’s own grounds.

The museum’s curator, Anand Sethi, is not just a military historian but also someone deeply connected to the place. His father, Balkrishan Sethi, was the first Indian to become the Cantonment Executive Officer in 1941-42. He lived in a cottage right next to the jail and would often share chilling tales of its inmates and guards with his son.

Years later, Anand Sethi started wondering what happened to the old prison after India became independent. Was it destroyed? Did anyone care? About two decades ago, he returned to Dagshai to find out. What he saw shocked him — the prison was falling apart. The forest had taken over the premises. Monkeys ran freely through the cells, the walls were leaking, and the structure was close to collapse.

But Sethi refused to let history die like that. He approached the local army commander at the time, Brigadier P. Ananthanarayanan, who later became a lieutenant general. Together, they started the process of saving and restoring the prison. Soldiers were sent in to drive out the monkeys, fix the broken parts, and clean the structure. Sethi personally supervised the work. The team painted, repaired, and made the building safe — but kept most of the original features unchanged. The idea was to preserve history, not erase it.

Thanks to their efforts, Dagshai Jail was brought back to life — not as a place of suffering, but as a museum that remembers the struggle and sacrifice of countless freedom fighters and rebels. Visitors can now walk through the same narrow corridors, see the same iron doors, and feel the deep silence that once surrounded the lives of prisoners.

Dagshai Jail is more than just a building — it’s a reminder of the price many paid for India's freedom. It's also a record of forgotten tales from around the world. Not only did Indians suffer there, but so did Irish soldiers who believed in their own country's freedom.

When we visit such places, we don’t just look at walls and doors. We connect with the people who once lived — and often died — inside. Their voices are silent, but their stories echo in every crack and shadow of the building. From British punishments to Mughal exiles, Dagshai has carried pain for centuries. Now, it offers reflection.

Dagshai is also a perfect example of how history can be saved. Without Anand Sethi's passion and the army’s support, the jail would have vanished under weeds and dust. Today, it teaches new generations about colonial oppression, the price of rebellion, and the strength of human spirit.

ALSO READ: Strengthening Himachal’s rural economy is top priority, says Chief Minister

ALSO READ: Himachal dam authorities asked to stay on high alert during monsoon season

Final thoughts

Tucked away in the cool hills of Himachal, Dagshai Jail is a museum of memory — grim but necessary. It speaks of the harshness of British rule, the courage of those who defied it, and the effort of one man to keep these stories alive.

Tourists today may visit Dagshai for its peaceful weather and mountain views, but inside this little jail museum, they will come face-to-face with a past that must never be forgotten.